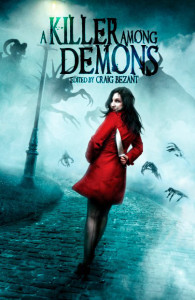

Edited by Craig Bezant

Published by Dark Prints Press 2013

Review by Martin Livings

In his introduction to A Killer Among Demons, editor Craig Bezant states that two of his greatest passions in fiction are crime and horror. Dark Prints Press has previously published well-received anthologies dealing in both of these genres – crime fiction in The One That Got Away and horror in the Australian Shadows Award-winning Surviving the End – but this is his first foray into combining the two, and personally I hope it’s not the last. A Killer Among Demons collects the work of a variety of authors, both local and international, all writing tales of supernatural crimes, ranging from the most personal and human – revenge, murder, obsession – all the way to the apocalypse itself, and even beyond.

The quality of stories in A Killer Among Demons is uniformly high. One fantastic element of every single story in the collection is the sheer invisibility of the writing, which is a staple of fine crime fiction especially. The reader is simply absorbed into the stories, swallowed whole, without being aware of the act of reading. As the much-missed Elmore Leonard once sagely advised, “if it sounds like writing, rewrite it”. This is a rule all ten writers in this collection clearly followed. Different readers will find different favourites – I personally lean away from the more standard gumshoe-style stories towards other more unique viewpoints and plots – but I can’t imagine any fans of crime or horror fiction being disappointed here.

Some of my personal favourites were “Cuckoo” by Angela Slatter, about a justice-meting body-swapping demon which finds itself up against something even worse than itself, Alan Baxter’s nigh-on Lovecraftian “The Beat of a Pale Wing”, which blends dark magical rituals with urban mobsters, and “Angel’s Town” by Madhvi Ramani, a bloodily violent tale of revenge from beyond the grave taken to its logical conclusion. The absolute highlight for me though was Stephen M. Irwin’s “24/7”, the longest – and closing – story in the anthology, which was a damn near perfect horror crime tale in my mind. Again, revenge takes a front seat (literally!) in this story of a man driven (again, literally!) to extremes by jealousy and rage. From mysterious beginning to inevitable but surprising end, “24/7” is a great piece of storytelling, and a fine end to the book.

With only ten stories nestled in its pages, and consisting of a mere 224 pages, this collection is short, sharp and deadly effective, like a bullet with a crucifix carved into it. This book is a must-read for fans of horror, crime and all things in between, and Bezant deserves great credit for gathering the work together and shaping it into a very unique and absorbing anthology.

(A brief disclaimer – Craig Bezant and Dark Prints Press are also the publishers of my collection Living With the Dead. But don’t hold that against them!)

- review by Martin Livings

Perth-based writer Martin Livings has had over sixty short stories in a variety of magazines and anthologies. His short works have been listed in the Recommended Reading list in Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, and have appeared in both The Year’s Best Australian SF & Fantasy, Volumes Two and Five, and Australian Dark Fantasy & Horror: 2006 and 2008 editions. His first novel, Carnies, was published by Hachette Livre in 2006, and was nominated for both the Aurealis and Ditmar awards. His collection, Living With The Dead, is available now. Find him at www.martinlivings.com/

.

Bloodstones

Bloodstones